Like most of history, the lens through which design has been evaluated is admittedly Eurocentric. Yet if we widen that lens, we find a more diverse landscape of design history that includes the contributions of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. Because these contributions weren’t perceived as affecting the evolution of European and U.S. design, they didn’t meet the criteria set for inclusion in the canons. Nevertheless, these castaways of design history can often be found in anthropology’s annals, and if we stitch the two together, an exciting narrative begins to unfold.

While there are certainly exceptions — the scholars Ron Eglash and Audrey Bennett, for example — most examiners of African art posit that any radical exhibitions of form, technique, or even math found in African art were intuition, and not the result of deliberate thought, action, or calculation. Bennett seeks to find a Black aesthetic whereby Black, Indigenous, and graphic designers of color can find belonging; for her, that aesthetic begins with understanding African mathematics as outlined in Eglash’s work. Similarly, in her essay “Searching for a Black Aesthetic in American Graphic Design Education,” Sylvia Harris, a trailblazer in the field of social impact design, points readers to several resources from the 1920s to the essay’s publishing in the 1990s that can be used to find some semblance of an aesthetic tradition. Harris’s position is that

[Black] students often exhibit insecurities that negatively affect their performance. In fact, they experience a problem common to many black design professionals: the feeling that they are not completely welcome in the profession. Lack of exposure to the prevailing aesthetic traditions also puts them (us) at a disadvantage. This outsider posture leads many black designers to compulsively imitate and assimilate mainstream aesthetic traditions to feel accepted and be successful. Often, black designers and students are trapped in a strategy of imitation rather than innovation.

For me, this disparity goes even further back. Yes, I agree that Black art and design students need to see working professionals of color producing at the highest levels of the field. What they also need — or maybe I should say here, what I needed when I was a student — is to see their ancestors reflected in the foundations of civilization, art, and design history that they are studying. One root of the psychosis outlined in Harris’s essay is the telling of a history that says to Black designers that they had, and, by extension, will continue to have, nothing to contribute. I hope that by providing examples of how Africans have contributed to the evolution of art and design history, it leads to a more inclusive telling of history.

Cave Painting

Art and design history frequently begin with cave paintings. In most design history texts, such as Philip Meggs’s popular reference book “Meggs’ History of Graphic Design,” while cave paintings from Africa are mentioned quite often, only cave paintings from Europe are shown. “Early human markings found in Africa are over two hundred thousand years old,” writes Meggs. “From the early Paleolithic to the Neolithic period (35,000 to 4000 BCE), early Africans and Europeans left paintings in caves, including the Lascaux caves in southern France and Altamira in Spain.”

While cave paintings have been documented in both art and design texts, they are not recorded as the beginning of the evolution of either craft but rather as an ancient mode of communication and storytelling.

In reality, cave paintings have been found wherever Indigenous populations were seen worldwide. These first peoples documented their existence from Brazil to Indonesia, India, Romania, Australia, and Africa. While recent evidence points to discoveries in Indonesia that are now said to be the oldest, previous research reserved that title for cave paintings found on the African continent. As described by the Bradshaw Foundation in “Where Is the Oldest Rock Art?,”

The painted stones from Apollo 11 in Namibia date to roughly 27,500 years. The oldest dated rock art in Africa was discovered in the Apollo 11 Cave in the Huns Mountains in southwestern Namibia. Seven grey-brown quartzite slabs, each smaller than an adult hand, were found with images drawn in charcoal and ochre during excavations in the cave in 1969 by German archaeologist W. E. Wendt. … Three samples of charcoal and ostrich eggshell found in the same layer were radiocarbon dated to between 27,500 and 25,500 years BP (Wendt 1976). More recent excavations have confirmed the dating of this layer and its Middle Stone Age associations.

This is just one documented instance. Further research on the subject reveals that rock art has been found across the African continent, from the Atlas Mountains in the north to the Drakensberg in South Africa, with a scale and complexity of form and color that rival the paintings in Lascaux. Additionally, not all rock art found in Africa is prehistoric; the Dogon people of Mali are, in fact, still producing rock paintings today. While cave paintings have been documented in both art and design texts, they are not recorded as the beginning of the evolution of either craft but rather as an ancient mode of communication and storytelling that serves as a lead-in to the study of ancient civilizations and their alphabets and writing.

The First Civilizations

While the oldest-known human specimen has been recorded in present-day Ethiopia, archaeologists and anthropologists continue to argue over which civilization was the oldest. Early researchers believed it to be the early civilizations of the Mesopotamians and Sumerians.

Biblical theology supported colonialism and slavery, noting the story of Noah and his sons, Shem, Ham, and Japheth. In Genesis, it is written that Noah cursed his grandson (son of Ham) Canaan with Black skin. This led scholars to believe that Ham and his offspring were cursed with Black skin and further justified their enslavement. Later, Western and Islamic traders and slave owners used the concept of the “Curse of Ham” to justify the enslaving of Africans. The Bradshaw Foundation explains that beginning in the 19th century, scholars generally classified the Hamitic race as a subgroup of the Caucasian race, alongside the Aryan race and the Semitic — thus grouping the non-Semitic populations native to North Africa and the Horn of Africa, including the Ancient Egyptians. According to the Hamitic theory, this “Hamitic race” was superior to or more advanced than the “Negroid” populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. In its most extreme form, in the writings of C. G. Seligman, this theory asserted that virtually all significant achievements in African history were the work of “Hamites.”

The telling of this history is essential because even though those theories have long been discredited and we no longer refer to Africans as Hamites, those theories have seeped into the overall retelling of history by which the achievements of the ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, and Sumerians are never told as the achievements of Africans. Similarly, the contributions of the people of sub-Saharan Africa are rarely spoken about with the same regard as those of northern Africa (ancient Egypt).

The Mesopotamians constituted a civilization that benefited from the genius of Sumerian immigration. Universally, historians have believed that the origin of the Sumerians remains a mystery. It’s difficult to believe that it remains a mystery to this day. Yet evidence suggests that the Sumerians called themselves “the black-headed ones.” Historians have theorized that black referred to the color of earth along the Nile. While the dirt along the Nile is black, a more logical explanation is that the reference to the head in relation to color relates to the color of their skin. As a result of the subgroupings outlined above, the level of advancement that these people brought to the region has made it difficult for researchers to accept them as Black or Negroid people. As George Barton, who was a professor of Semitic languages at Bryn Mawr College, wrote in 1928,

It is clear that the Sumerians were highly civilized when they entered Babylonia; they knew the arts of agriculture by 3500 BC; they would make beautiful objects of gold and silver, surpassing in craftsmanship and beauty anything found in Egypt until centuries later; they could write; they had invented the principle of the real arch and dome, and they had invented the use of the wheel and the chariots.

By 3100 BC, we began to see entries of Egypt, specifically Egyptian hieroglyphics. “By the time King Menes unified the land of Egypt and formed the First Dynasty around 3100 BCE, a number of Sumerian inventions had reached Egypt,” writes Philip Meggs. In the telling of the story of King Menes, little is documented about Upper and Lower Egypt themselves, leading a non-questioning student to believe that nothing of note came out of these civilizations, or that they were not civilizations at all and that the writer is simply speaking about the unification of territory. The word unification, however, suggests that there may have been an ongoing conflict between the two unnamed groups of people. Chancellor Williams writes in “The Destruction of Black Civilization” that

there were Blacks who neither fled before the Asian advance nor submitted to enslavement. These, also rejecting amalgamation as the process of transforming the race, stood their ground fighting back and were generally wiped out. In short, the Africans held Upper Egypt (South) while the Asiatics held Lower Egypt (North).

Chancellor Williams goes on to observe that, “Finally, the great triumph came when African King Menes defeated the Asians decisively and united all of Egypt under African rule again, beginning the historic First Dynasty.”

It is important to note that while textbooks universally refer to this territory as Egypt, Egypt as a territory did not exist before the arrival of the Greeks. The unification of Upper and Lower Egypt resulted in the building of Memphis. Egypt was not a single civilization of Indigenous people but instead the culmination of years of immigration of different cultures and ethnicities from the Sumerians to other unnamed peoples from the eastern and lower regions of Africa as well as Asia.

Alphabets

In Egypt, we find both writing and architecture that surpasses anything produced by any other civilization. The hieroglyphics as they are presented are quite sophisticated and shown in comparison to cuneiform, the writing system of the Sumerians, the civilization that directly precedes it. What we do not see, though, is the evolution of hieroglyphics, which undoubtedly would have been developed in either Upper or Lower Egypt before its unification in 3100 BC, or by some other ancient civilization that immigrated to Egypt. In his book “Afrikan Alphabets: The Story of Writing in Afrika,” Professor Saki Mafundikwa writes that “pictographs and symbols — used in pictographic rock art, scarification, knotted strings, tally sticks, and symbol writing — are considered together as forerunners of writing in Afrika. They form the roots, both directly and indirectly, of Afrikan writing systems.”

Protowriting and petroglyphs can be seen as the precursors to pictographic writing styles like hieroglyphics.

Protowriting and petroglyphs can also be seen as the precursors to pictographic writing styles like hieroglyphics. While the word hieroglyphics is most often associated with Egypt, hieroglyphs as a style of writing are not exclusive to Egypt. The Mayans have their own hieroglyphics that postdate the ones found in Egypt. But the Dogon in Mali have a system of hieroglyphics that are quite like the ones found in Egypt. While the two styles differ in execution, with the Egyptians offering more sophistication in the color and depth of their carved reliefs, they are similar in that they both utilize a system of imagery to represent all things in the universe. The most interesting of these is math and science. Studies of the Dogon culture reveal close relationships between Dogon words and Egyptian words, and many Dogon drawings appear as glyphs in Egyptian words.

Laird Scranton’s radical reinterpretation of Egyptian Hieroglyphs came directly from his studies of Dogon cosmological symbols. Their priests use cosmological drawings, symbols they have used for thousands of years. While it is impossible to ask the ancient Egyptians to explain their beliefs, Dogon priests can explain their cosmology and how their symbols are written and pronounced.

Scranton asserts that the link between the Dogon and Egyptians exists because the Dogon are said to have come out of a class of ancient Egyptian priests who had specialized knowledge and, in his opinion, left Egypt. While there is no evidence to back up his claim, I would argue that the style of the Dogon hieroglyphs seems closer to rock painting, and had they been taken out of Egypt, the technology for creating the reliefs and so on would have come along with it. There is no doubt, however, that the Dogon come from an ancient priesthood, and it is no surprise that many of the rock paintings found across the African continent can be associated with shamanistic rituals, with many of the sites still being used for spiritual purposes today. I believe that the Dogon may be one of the unnamed civilizations of sub-Saharan Africa that immigrated into and influenced ancient Egypt.

Looking forward to the present day, Africa now has over 2,000 living languages and possibly an equal number of alphabets that are yet to be included in the design canons.

Illuminated Manuscripts

The word illuminated as it pertains to manuscripts used to refer only to gilded manuscripts, but, writes Meggs, “today this name is used for all decorated and illustrated handwritten books.” Their study in graphic design history begins with the Vatican Vergil created in the early fourth or fifth century, and concludes in 1450 when typography and printed books start to replace manuscripts. Once movable type was invented, the Gutenberg Bible became and still is one of the world’s most valuable books. Ethiopian bibles, specifically the Garima gospels, are argued to be the world’s oldest surviving illuminated manuscript. To date they are not mentioned in most major design canons.

The Golden Section

A great deal has been learned from Egyptian and Dogon hieroglyphics about our cosmology and belief systems. Hidden in those systems are ancient math and science. The earliest example of math found on the African continent is the Lebombo bone. Discovered in Swaziland, the Lebombo bone is a 37,000-year-old fibula of a baboon bearing 29 clearly defined notches reminiscent of calendar sticks still used in Namibia today. The most common example of African math, though, can be found in the pyramids of Egypt.

The pyramids of Giza are the pièce de résistance of ancient African architecture. Built during the Old Kingdom to house the pharaohs, these pyramids are works of art that tell the story of religious beliefs at the scale of political power, unmatched by anything else in its time. They are also a representation of the extremely technological and mathematical skills of the Egyptians, as evidenced by their ability to stand the test of time and their use of the golden section in the building of the Great Pyramid. As explained in the “Britannica,” the golden ratio is

Also known as the golden section, golden mean, or divine proportion, in mathematics, the irrational number (1 + √5)/2, often denoted by the Greek letter φ or τ, which is approximately equal to 1.618. It is the ratio of a line segment cut into two pieces of different lengths such that the ratio of the whole segment to that of the longer segment is equal to the ratio of the longer segment to the shorter segment.

Originally credited to the mathematician Euclid, there has been much debate surrounding the golden ratio’s application to the pyramids. Some scientists believe that the math is close but not exact. “The height of an isosceles triangular face is approximately phi (φ). The height of the pyramid is approximately the square root of phi. The height can then be found as √ φ = 4 ÷ π. And the slope of the pyramid is very close to the golden pyramid inclination of 51°50´.”

While the erosion of the pyramid itself can account for the approximation of the math, scientists further argue that there is no written evidence of the golden section in any of the Egyptian texts.

While the golden section can be said to be an anomaly on the Giza Plateau, the sight of the Great Pyramids, it can be found across a number of African artifacts that also predate Euclid.

Logone-Birni

Logone-Birni is a city in Cameroon founded by the Kotoko people. The Kotoko create massive compounds by a process called “architecture by accretion,” where the builders add walls onto existing ones to expand the footprint of the compound. It’s hard to discern in the illustration below, but when the outlines of the compound are drawn, we see the self-similar scaling (making the same pattern at different scales). The Kotoko men describe their architecture in terms of “a combination of patrilocal household expansion and the historic need for defense,” writes Ron Eglash in his book on African fractals. “A man would like his sons to live next to him, they said, and so we build by adding walls to the father’s house.” The sons using pathways and architecture to form a barrier of protection around their father is a beautiful notion that results in a spiral effect around the compound that resembles a golden section. As Audrey Bennett puts it in her essay “The African Roots of Swiss Design,”

The recursive construction of the palace — from tiny rectangles to larger and larger rectangles — naturally lends itself to the golden rectangle construction for the overall form, even though the match along any one wall is far from perfect. This method of organically growing architecture is typical of building layouts in Africa; indeed, many of its design patterns include this organic scaling, probably because it links to concepts of fecundity, fertility and generational kinship that are commonplace in African art and culture.

There is a behavioral pattern also associated with the movement through the spiral. As the person enters and draws closer to the chief’s quarters, it is customary that their behavior becomes more reserved until finally the visitor enters the chief’s quarters shoeless and speaking in hushed tones.

Like the pyramids of Giza, the golden ratio scaling shown here is an approximation, although the viewer can see the spiral from the aerial photo. While the inhabitants of such structures may not speak of the building in mathematical terms, the repetition of such structures in different communities is what, in my opinion, makes these ancient traditions that have been taught to the citizens of Cameroon for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

Design Principles

Graphic design is taught as a series of principles — hierarchy, repetition, balance, pattern, white space, color, and proportion, to name a few. Architectural design shares many of the same principles too, with buildings like the Taj Mahal and Saint Basil’s Cathedral topping the list of the world’s most notable structures. The pyramids of Giza also appear on these lists, yet as I mentioned previously, an examination of this kind rarely looks below North Africa for examples of excellence in the field.

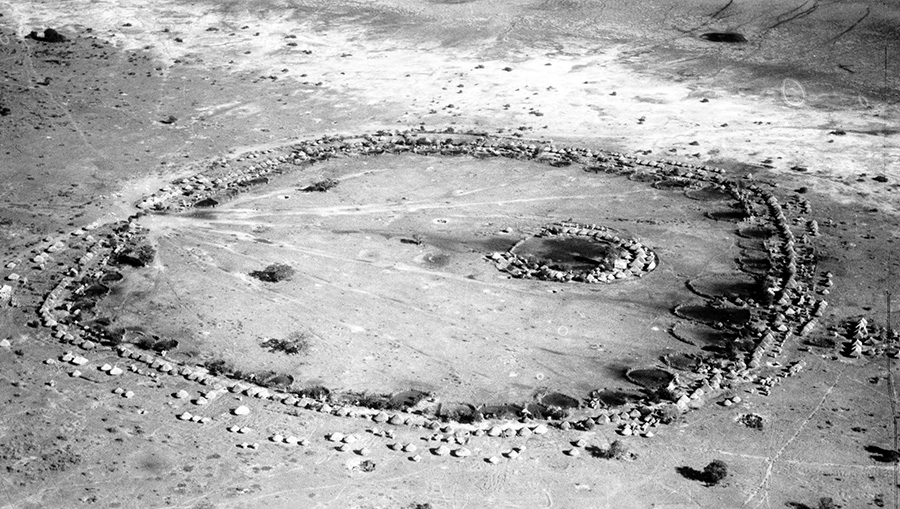

The Ba-ila settlements of southern Zambia are designed as an enormous ring of rings. Each ring is made up of a series of smaller ones. The rings are ordered or sized according to one’s social standing in the community (a status gradient). The straight lines to the front are fencing. Next, there are small rings, used for livestock or things of a lower status. The rings after that are used for storage. As the rings become larger and larger, they begin to be used as the family’s living quarters, with the largest rings in any set being used for the most important person in that settlement. The settlement next to that is ordered the same; since the size of the ring is larger, the occupants of that ring are of higher standing in the community. Their animal quarters are larger because they have more livestock, and their living quarters are larger because they are more important. The settlements continue to get bigger and bigger as you move up the curve of the circular village. Finally, the rings at the back or center are occupied by the chief’s extended family. The largest ring is situated at the center of the village, and that ring is reserved for the chief and his family. As noted in the drawing below, each ring has an altar at the back. And the chief’s quarters are placed in the position of the village’s altar.

Eglash notes,

As a logician would put it, the chief’s family ring is to the whole settlement as the altar is to the house. They view this as a recurring functional role between different scales within the settlement. The chief’s relation to his people is described by the word kulela, a word we would translate as “to rule.” However, it has this only as a secondary meaning — kulela is primarily to nurse and to cherish. The same word [is] applied to a mother caring for her child, making the chief the father of the community. This relationship is echoed throughout family and spiritual ties at all scales and is structurally mapped through self-similar architecture.

The three core elements of each settlement are the ring structure, the use of size gradients in the architecture, and the placement of the altar. From the smallest animal corral to the chief’s quarters, every settlement within the village mimics this identical structure. In the figure below, the first iteration shows a single house. Note that the single line of the sacred altar is situated at the back of the house. In the second iteration, the altar has become a house, with other circular dwellings surrounding it. In the third iteration, you will see that the main house becomes the chief’s family village and sits inside the village as a whole.

This Ba-ila village is a perfect example of self-similarity. The status gradient is applied to both architecture and community. The social scaling is mapped onto the architectural geometric scaling, and the nested architecture seems to provide a fortress for the chief’s quarters.

Mathematically speaking, Ba-ila is an ancient fractal. Although Ba-ila is not credited with the invention, fractals have been used in African culture as a design tool in sculpture, architecture, pattern making, and divination for centuries.

Although Ba-ila is not credited with the invention, fractals have been used in African culture as a design tool in sculpture, architecture, pattern making, and divination for centuries.

Mathematics is not the only lens through which we can view Ba-ila. From a design perspective, Ba-ila is a stunning representation of modern-day architectural principles like form follows function — a principle of design that states that the shape of a structure should be determined by its use or function. The village is also symmetrical in its construction with excellent use of both positive and negative space (white space). Moreover, we see pattern, hierarchy, and balance exhibited harmoniously within this single composition.

The Ancient African Aesthetic

Africans have made contributions to design since the beginning of civilization, and these examples represent only a handful of the information that exists. These instances prove that ancient African aesthetics represent a much too often overlooked sophistication of the continent that I would love to see incorporated into designs and design textbooks today. The position that African art is the output of mathematicians, intellectuals, and thinkers has never been suggested, and it begs exploration. The goal here is not to compete with or delete any of design’s past but rather to begin to add a more inclusive perspective of the field.

Jillian M. Harris is a creative director based in New York City and has been a graphic designer for 25 years. Her research focuses on the ancient African contributions to design. This article is excerpted from the volume “An Anthology of Blackness.”

No comments:

Post a Comment